Frederick Douglass, perhaps one of America’s greatest civil rights leaders, presented a speech in Rochester, New York, on July 5, 1852 entitled, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro.” The first part of his speech praises what the founding fathers did for this country, but the speech soon expands into a denunciation of the attitude of American society toward African heritage enslavement and equality. In his historic speech, Douglas points out the bitter irony of America celebrating the nation’s birth of freedom and independence, while embracing the enslavement of nearly four million declaring:

“The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn. To drag a man in fetters into the grand illuminated temple of liberty and call upon him to join you in joyous anthems, were inhuman mockery and sacrilegious irony.”

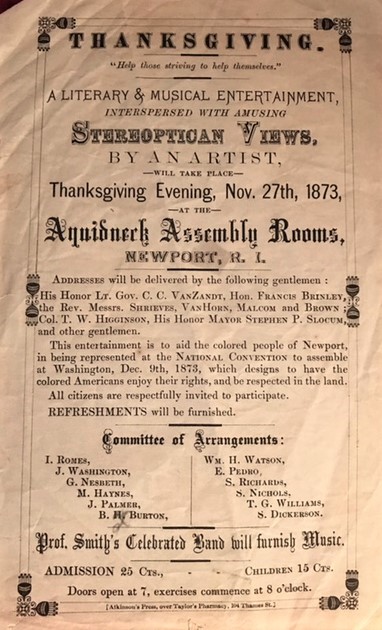

Fifty years later, after the abolishment of slavery and the ratification of the 13th, 14th and 15th amendments to the United States Constitution, a group of leading African heritage political and social justice leaders in Newport, Rhode Island, led by one of Fredrick Douglas’s closet civil rights allies, George T. Downing, published a narrative entitled, “An Expression from the Oppressed.” Like Douglas before them, the Rhode Island men point out the unfair treatment of citizens of color by a legal and political system that still embraces Jim Crow laws and separate and unequal life between the races.

The 1902 call to action reminded the community that the rampant discrimination against citizens of African heritage still existed across Rhode Island and America. As in the case of Douglas’s plea that America would never achieve true freedom and unity until slavery was abolished, the Newport men added that Rhode Island and America would not achieve freedom and unity until laws were in place to ensure that all men were created and treated as equals stating:

“We ask, where does the right obtain to look upon the complexion of citizens of a common country and make individual distinctions among them? We are colored, but we feel ourselves the peers of our fellow countrymen. We refer to the proud fact that Negro blood was the first blood to flow for American Independence and that it is flowing ever since, freely in a very marked manner in defense of the Nation in all its battles. Why treat us as you do?”

Frederick Douglas’s narrative in 1852 Rochester and George Downing’s narrative in 1902 Rhode Island takes on added significance today during a Black Lives Matter movement that is yet again calling for social justice and equal rights for African heritage citizens – but is anyone listening?